CELEBRITY STYLE

why are we so interested in celebrities?

I love a decent date. one in every of my uncomparable favorites is from Mark Twain: “If I wrote this long letter, it had been as a result of I did not have time to create it shorter,” he once told a lover.

It is a beautiful irony that I even have perennial to my friends and colleagues. Typical dyad, you may say.

Only it’s not. i used to be recently told that truth author of the quote may be a lesser-known French thinker named mathematician, UN agency wrote the phrase during a letter to a lover in 1657. I looked it up and confirmed it to be true.

I’m certain several of you’re aware of Einstein’s good saying: “The definition of mental illness is doing constant issue over and once again and expecting a special result.” it’s most likely the foremost illustrious issue he aforesaid, when the formula “E = mc2”.

But there’s no record that it had been he UN agency spoke these words. the primary time the phrase appeared in print was in 1981, during a Narcotics Anonymous pamphlet, some twenty five years when his death. And there ar more similar examples.

Winston Churchill, writer and Luther King have most likely aforesaid but half what’s thought. Quotes fight importance after they return from those that became illustrious for his or her wit and knowledge.

Misattributing quotes exemplifies our tendency to allow celebrities an excessive amount of credit.

Fame may be a powerful cultural magnet. As a hypersocial species, we tend to acquire most of our data, ideas, and skills by repeating others, through trial and error. However, rather more attention is paid to the habits and behaviors of celebrities than to those of standard members of our community.

That is why one thing is incredibly doubtless to become widespread if it’s related to a well known person for one reason or another, albeit the association is wrong, as within the case of dyad and Einstein. This raises the question of whether or not what’s aforesaid is as vital as UN agency aforesaid it

celebrity culture

Another example of the manner characters act as cultural magnets is that we regularly copy traits that have very little or nothing to try and do with what created them palmy within the initial place: the garments they wear, their hairstyles, the manner they speak, etc. .

That’s essentially why firms rummage around for stars to endorse their product. Celebrities ar forever on tv and within the media. obtaining them to wear a complete of watch or jeans may be a nice promotion.

But it’s not solely regarding golf shot product publicly read. there’s no manner of knowing – from look TV photos or newspaper photos – what reasonably underclothes David Beckham wears, what low St. George Cyclone drinks or what Benchley’s fragrance smells like.

Companies look to celebrities to advertise these varieties of product as a result of they understand that our perception of import is actively influenced by fame. Celebrity endorsements not only make products more visible, but also more desirable.

Why is this happening?

Celebrity culture is often portrayed as something relatively new, a product of a media-saturated society.

Although I agree that celebrity culture has been shaped by the modern world, the truth is that it is rooted in the most basic human instincts, which have played a key role in the culture’s acquisition and have been crucial to the evolutionary success of our species.

We could focus on the anthropology of prestige, a form of social status based on the respect and admiration of members of one’s own community. It is particularly interesting to anthropologists because it appears to be a feature unique to our species, while also being universal to all human cultures.

By dint of prestige

In other primates, social hierarchies are usually based on dominance, which is different from prestige, since it implies fear and threat of violence.

Individuals give in to more dominant animals because if they do not let them have what they want, it will be perceived that they are challenging their status, which they will defend by force. Many types of hierarchies in human society are similar.

However, unlike other primates, we also differentiate social status in terms of reputation.

In contrast to dominance, prestige arises voluntarily. It is freely given to individuals in recognition of their achievements in a particular field and is not backed by force.

How did these types of systems come about? The most convincing theory indicates that prestige developed as part of a package of psychological adaptations for cultural learning. This allowed our ancestors to recognize and reward people with superior skills and knowledge, and to learn from them.

New discoveries and techniques – for example, how to harness the medicinal properties of plants or how to optimize the design of hunting weapons – spread through the population and allowed successive generations to build on and improve on the knowledge of their predecessors.

Although the preference to imitate some prestigious individuals has helped promote the spread of adaptive behaviors, anthropologists suggest that it may make us susceptible to copying traits that are not always useful in themselves, and may even be harmful.

The reason is that prestige-biased learning is a strategy directed at models of success and not at specific traits. This is what makes it such a powerful and flexible tool, as the traits that make a person successful can vary considerably in different environments, so it makes sense to copy the one that seems to be doing the best at a given time and place.

However, this strategy can lead people to adopt all the behaviors exhibited by a role model, including those that have nothing to do with their success.

For example, men may watch a successful hunter perform some kind of incantation as he touches up his arrowheads, and adopt both the ritual and the techniques when preparing their own tools.

This trend, I think, explains our interest in what sports stars and singers wear, what car they drive, and where they shop.

In the past, useless traits acquired as a result of prestige-biased learning were offset by the benefits of learning useful skills. Therefore, in the long term, it turned out to be an effective adaptation strategy.

However, I am far from convinced that our attraction to prestige continues to promote superior cultural knowledge and skills.

famous vs. model to follow

The modern world is very different, and I believe that the originally adaptive bias to imitate successful people has now morphed into an unhealthy obsession with celebrities, whom we pay far more attention than they deserve.

Let me illustrate the point through a diet analogy. We have an evolutionary preference for sugary and fatty foods, because they were what motivated our ancestors to seek meat and ripe fruits, rich in essential nutrients. But in today’s world, these previously adaptive tastes have given rise to a massive obesity epidemic.

Similarly, we can think of the media as a kind of junk food for the mind. It’s quick, convenient, but not exactly nutritious. We get lost in images of wealth and success because we have an appetite for prestige. But are celebrities really good role models?

In posing this question, I am not referring to the highly publicized cases of misbehavior, but to the purpose of the star.

In ancient societies, the blueprint for a good role model was relatively well defined: a good hunter or gatherer, for example. In our society, with its complex class system, division of labor and mix of cultures, the criteria for success are much more varied. Many celebrities have achieved their success in fields like sports and music, which few of us can emulate.

But we still imitate what we can, because our brains are hardwired to associate prestige with adaptive behavior. And since fame is the main sign of prestige, the more famous they are, the more people they attract.

No wonder then that fame has become an end in itself. In the modern world, it doesn’t really matter what you’re famous for.

Indeed, although celebrities receive more attention and prestige than at any other time in human history, we are often being told that they should not be role models.

But -seen from the evolutionary anthropological perspective that I have outlined- you may ask, how do you become famous without being a role model?

Why benefit them with prestige, if we are not reciprocated with something useful?

Pondering those questions, we might reflect on these words of Samuel Johnson, one of England’s greatest literary figures: “Getting a name is one of the few things that cannot be bought. It is the free gift of humanity, which must be deserved before it is bestowed”.

CELEBRITY STYLE

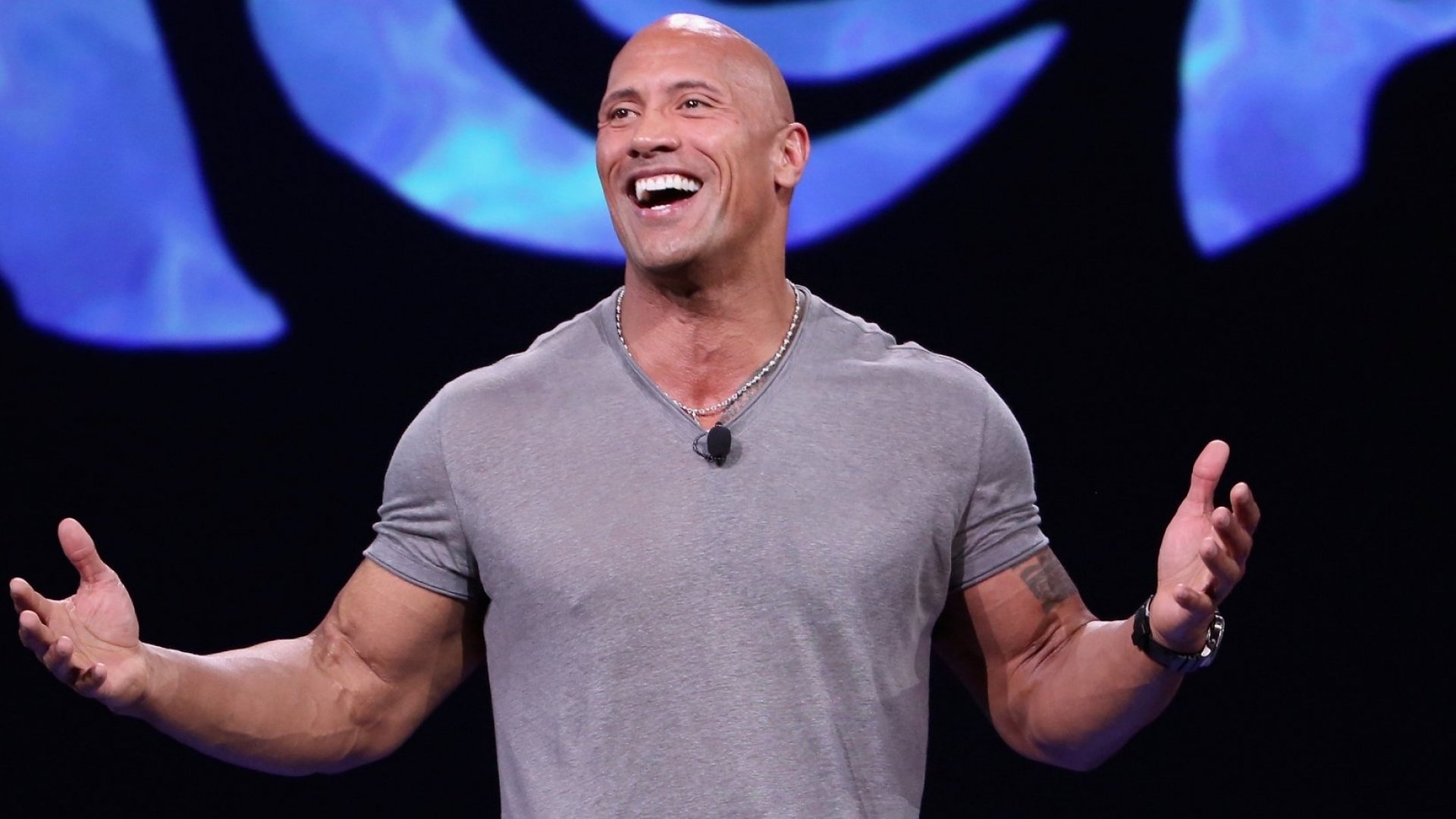

How Is The Rock Johnson?

An In-Depth Look At The Life And Career Of One Of Hollywood’s Biggest Stars

Dwayne The Rock Johnson is a name that is familiar to millions of people around the world. From his early days as a professional wrestler to his current status as one of the biggest movie stars on the planet, Johnson has captivated audiences with his charm, charisma, and larger-than-life personality. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at the life and career of this legendary performer, examining everything from his early days as a football player to his rise to fame in Hollywood.

Early Life and Career

Born in California in 1972, Dwayne Johnson grew up in a family of wrestlers. His father, Rocky Johnson, was a professional wrestler in his own right, and his grandfather, Peter Maivia, was a well-known Samoan wrestler. Despite his family’s deep ties to the world of wrestling, Johnson initially pursued a career in football. He played for the University of Miami in the early 1990s before being cut from the Calgary Stampeders of the Canadian Football League.

Wrestling Career

After his football dreams were dashed, Johnson decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and pursue a career in wrestling. He signed with the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) in 1996 and quickly became one of the most popular wrestlers in the company. His larger-than-life persona and trademark catchphrases made him a fan favorite, and he won numerous championships during his wrestling career.

Acting Career

In the early 2000s, Johnson began to make the transition from wrestling to acting. He made his big-screen debut in 2001’s “The Mummy Returns” and quickly became a sought-after leading man in Hollywood. Over the years, he has appeared in a wide range of films, from action movies like “Fast and Furious” and “Jumanji” to comedies like “Central Intelligence” and “Moana”. In addition to his movie work, Johnson has also appeared on TV shows like “Ballers” and “Young Rock“.

Personal Life

Despite his busy career, Johnson has always made time for his family. He has three daughters with his wife, Lauren Hashian, and he frequently shares photos and updates about his family life on social media. In addition to his family, Johnson is also known for his philanthropic work. He has donated millions of dollars to various causes over the years, including the Make-A-Wish Foundation and the Boys and Girls Club.

Conclusion

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson is a true icon of our time. From his early days as a football player to his rise to fame in Hollywood, he has captured the hearts and minds of people all over the world. Whether he’s in the ring, on the big screen, or just hanging out with his family, Johnson always brings his trademark charisma and energy to everything he does. It’s clear that he has a bright future ahead of him, and we can’t wait to see what he’ll do next.

FAQs

Q: What was Dwayne Johnson’s first movie? A: Johnson’s first movie role was in “The Mummy Returns”, released in 2001.

Q: How many championships did Johnson win in his wrestling career? A: Johnson won numerous championships during his wrestling career, including eight WWF/WWE championships.

Q: Who is Dwayne Johnson’s wife? A: Johnson is married to Lauren Hashian, a singer and songwriter.

Q: What is Dwayne Johnson’s net worth? A: As of 2023, Johnson’s net worth is estimated to be around $320 million.

Apologies for the mistake. Here’s the continuation of the article:

Q: What other TV shows has Dwayne Johnson appeared in? A: In addition to “Ballers” and “Young Rock”, Johnson has also made guest appearances on shows like “Saturday Night Live” and “Star Trek: Voyager”.

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson has made an indelible mark on the world of entertainment, and his legacy is sure to endure for many years to come. Whether he’s taking down opponents in the wrestling ring or saving the world on the big screen, he always brings his unique blend of humor, heart, and heroism to everything he does. So how is The Rock? He’s doing just fine, and we can’t wait to see what he’ll accomplish next.

CELEBRITY STYLE

Celebrity style wigs

At Celebrity Style Wigs

At Celebrity Style Wigs, we know that wigs are not just for those suffering from hair loss. In fact, wigs have become a popular accessory in the fashion world, allowing people to change up their look without committing to a haircut or color change. We understand that finding the right wig can be a daunting task, especially with the abundance of options available online. That’s why we’re here to help guide you through the process and help you find your perfect celebrity-style wig.

First, let’s talk about the different types of wigs available. There are synthetic wigs and human hair wigs. Synthetic wigs are made from man-made fibers, which makes them more affordable and easier to care for. They also come pre-styled, so you don’t have to worry about styling them yourself. Human hair wigs, on the other hand, are made from real human hair and are more versatile when it comes to styling. They also tend to last longer than synthetic wigs with proper care.

When choosing a wig, it’s important to consider the cap construction. The cap is the base of the wig, and it’s what the hair is attached to. There are different types of cap constructions, including lace front, full lace, and monofilament. Lace front wigs have a lace front that creates a natural-looking hairline, while full lace wigs have a lace cap that covers the entire head, making them the most versatile option for styling. Monofilament wigs have a thin, breathable cap that allows for a natural-looking part.

Another important factor to consider when choosing a wig is the length and style. Short wigs are low maintenance and perfect for those who want a chic, modern look. Medium-length wigs are versatile and can be styled in a variety of ways. Long wigs are great for those who want a dramatic, glamorous look. When it comes to style, there are countless options available, including straight, wavy, curly, and even braided wigs.

At Celebrity Style Wigs, we pride ourselves on offering a wide variety of celebrity-inspired wigs. Whether you’re looking for a Kim Kardashian-inspired long, sleek wig or a Rihanna-inspired short, edgy wig, we’ve got you covered. We also offer wigs in a variety of colors, from natural shades to bold, fashion-forward hues.

One thing to keep in mind when purchasing a wig is that it may require some styling to achieve your desired look. It’s important to invest in high-quality styling tools and products to ensure that your wig looks its best. We recommend using a wide-tooth comb or wig brush to detangle your wig, and a heat protectant spray when using hot tools.

When it comes to caring for your wig, it’s important to follow the manufacturer’s instructions. In general, you’ll want to store your wig on a wig stand or mannequin head when not in use, and wash it every 6-8 wears with a specially-formulated wig shampoo and conditioner. It’s also important to avoid exposing your wig to high temperatures, such as those from a blow dryer or flat iron.

In conclusion, at Celebrity Style Wigs, we believe that everyone deserves to feel confident and beautiful. Our wide variety of celebrity-inspired wigs are sure to help you achieve the look you desire. With the right wig, styling tools, and care, you can rock any look with confidence.

Celebrity wigs human hair

Sure, I can help you with that! If you’re looking for celebrity wigs made from human hair, there are many options available on the market. Human hair wigs are known for their natural look and feel, and they can be styled and treated just like your own hair.

When it comes to celebrity wigs, you can find options that mimic the hairstyles of your favorite stars. From long and flowing locks to short and edgy cuts, there are celebrity-inspired wigs for every taste and style.

Some popular brands that offer high-quality celebrity wigs made from human hair include Raquel Welch, Jon Renau, and Ellen Wille. You can also find many options on websites like Amazon and WigOutlet.com.

When shopping for a celebrity wig, be sure to pay attention to the color, length, and style to make sure you’re getting the right look. You may also want to consider the quality of the wig’s construction and the type of cap it has, as these factors can affect the overall look and feel of the wig.

CELEBRITY STYLE

How Does a Doja Cat Look With No Makeup?

Have you ever seen a Doja Cat no makeup look? Many celebrities can’t go without using makeup, even when they are going to shop for groceries. Doja Cat is no exception, as she is always with makeup, especially when she’s performing for her fans.

As a popular lyricist and singer, Doja is never caught unawares when it comes to dressing up for her show. Well, people can’t blame her because the showbiz industry is a glamorous one. You need to showcase your looks, talent, and personality. Doja Cat has all three in abundance. She is talented, glamorous, and has a showbiz personality. Her talent is evidenced by the way her songs top the charts for months on end. Not only that, she is an excellent music writer with beautiful lyrics.

What you should know about Doja and Doja Cat no makeup look

Cat was born in America, and sings and raps for a living. Her songs are infamous for being outlandish, yet they always top the charts. What many might not know is that Doja Cat is her showbiz name. She was named Amala Dlamini at birth.

Educational background

Doja dropped out of college to pursue her dream as a singer. This means that she didn’t get to complete her college degree. Nevertheless, her courageous decision to quit college paid off big time due to her hard-working spirit. She devoted her time and energy to writing and making music. Today, Cat remains one of the best songwriters, singers, and rappers. Whenever people listen to Doja Cat’s songs, they feel happy and smile.

Doja Cat Dolled up look

Doja Cat is a very pretty woman, even without makeup. Hence, many people want to achieve a Doja Cat no makeup look. However, when she is all glamoured up, the makeup enhances her beautiful face. But many would love to know if Doja Cat also goes out without makeup. They want to see Doja Cat with no makeup.

Doja Cat with no makeup

Don’t be surprised if you see a Doja Cat’s no makeup photos online because you’ll be stunned. There are several pictures of Doja with no makeup on the internet, especially on social media.

Some of them include:

It is nothing new to see celebrities on Instagram live with make-up. They also use Instagram filters to make them more beautiful and flawless. It is very rare to see a famous person come online to do a video with her bare face.

Only Doja Cat and a few are the exceptions to the normal celeb appearance. Doja is known to be an engaging Instagram live host. She has appeared in lots of her live shows with make-up on. Yet, what makes her different is her courage to show her face without makeup live on Instagram.

Doja’s Fan’s Reactions

She stunned her fans the day she did that. Those who attended her live session were awed by Doja Cat no makeup face. The look became sensational on Instagram and some people tried to copy that look. They got inspired by Doja’s video and tried to upload their face without makeup.

Doja’s Reaction

Doja was not embarrassed to reveal her Doja Cat no makeup face to her Instagram followers. This proves that stars are human beings too and some are down to heart enough to connect with their fans. Not all stars get embarrassed when caught on camera without makeup. Few are even as brave as Doja and upload their no-makeup face themselves.

Social media picture

If you search online, you will find a picture of Doja wearing a white top without makeup. This picture was personally uploaded by Doja on her social media pages. Fans can see Doja looking confident, even without makeup on. While social media users sometimes troll celebrities that upload their no-makeup pictures, they didn’t troll Doja. Instead, they complimented Doja’s picture and liked the Doja no makeup photo. Even if they trolled her, she doesn’t care.

Selfie

Doja has taken several selfies on her Instagram page. This time around, she posted a selfie with her real face. Although this isn’t her first time doing this, people were still surprised nonetheless. In addition, Doja effortlessly posted a selfie with her camera without makeup. Besides, the picture was overflowing with her confidence. Doja told her fans not to feel embarrassed when they click their pictures without makeup. She said they are beautiful with or without makeup.

Doja’s photo with acne

Doja doesn’t only upload pictures when her face is flawless. She revealed her face that had acne to the public. Normal people with acne are not okay with taking their pictures without makeup, not to talk of celebrities. A while ago, she posted on her Instagram a photo of herself with acne on her face. Doja admitted that she was not ashamed of showing her flaws to her fans. She encouraged others looking through the same thing, not to feel scared to let the world see their flaws.

Doja further stated that she understands that acne can reduce people’s self-esteem. But that doesn’t mean that it should make them feel scared. Her fans applauded her move and promised to change the public’s perspective about standards of beauty.

Her Radiant picture

Doja Cat has selfies of her radiant face without makeup. Fans can see her face with her pores and yet, they find her so beautiful. Her natural face inspired people to upload theirs on the internet.

Conclusion

All in all, Doja didn’t say there is a problem with using makeup. But with the way society thinks that a woman without makeup is not beautiful, we need to change the narrative. Society has forgotten that beauty comes within. Hence, she tries her best to encourage ladies to show the world their natural beauty or face. There is nothing to be ashamed of. So you can copy the Doja Cat no makeup look and upload it on social media.

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoAdmiral casino biz login

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoHow Much Does The Rock Weigh

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoDownload Popular Latest Mp3 Ringtones for android and IOS mobiles

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoTop 10 Apps Like MediaBox HD for Android and iPhone

-

LIFESTYLE2 years ago

LIFESTYLE2 years agoWhose Heartland?: The politics of place in a rural–urban interface

-

Fashion3 years ago

Fashion3 years agoHow fashion rules the world

-

Fashion Youth2 years ago

Fashion Youth2 years agoHow To Choose the Perfect Necklace for Her

-

Fashion Today2 years ago

Fashion Today2 years agoDifferent Types Of lady purse