News

How Is Fashion Actually Measuring Up To Its Climate Goals?

It’s no secret that fashion needs to drastically cut greenhouse gas emissions. As such, several leading brands have pledged to halve their emissions by 2030 and achieve zero emissions by 2050. It is part of the United Nations Fashion Industry Charter on Climate Change, which raised its ambitions last year.

Now at Cop27, the United Nations climate change conference in Egypt, the question is how fashion will achieve its goals. Effective gas emissions must be reported annually, with 89% of companies submitting data this year (non-compliant companies are excluded of the signatories). . “These accountability requirements are important because they give brands momentum to move forward and do the right thing,” Lindita Zaferi Salif, head of the UN Fashion Charter on Climate Change, told Vogue.

The latest data is yet to be collected by the United Nations, but initial analysis shows that, unfortunately, most brands are far from meeting their obligations after the recovery of post-quarantine emissions in 2020. Proposed. It turns out that only Levi’s, one of the fashion charter signatories, plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 (the target). 1.5C limits set by the Paris Agreement). In fact, the campaign team found that emissions from eight brands actually increased in the past year. It is worth remembering that these companies have in fact signed commitments to protect the environment. Much of the industry is not.

“Emissions often went down during Covid, [but] actually went up,” Stand.Earth corporate climate activist Rachel Kitchin said. The push for further growth is the elephant in the room that the industry has yet to address: “[Brands] need to act now to stop the growth of fossil fuels, switch to renewable energy and supplies. It is critical to take carbon off the chain and really see how we use fossil fuel derived materials,” she continues.

While some brands have questioned the methodology used by Stand.Earth (H&M, for example, has stated that “increased emissions due to the [post-coronavirus] recovery will affect how we see the future, or not.”) There is more work to be done. to be done. According to the 2020 UN Fashion Charter’s own data, only 15% of signatories chose the 1.5C path, while about 30% opted for the 2C path.

With textile manufacturing and processing making up a large part of the industry, materials are a key piece of the puzzle. Last year, the Fashion Charter signatories made new commitments to ensure that all priority materials such as cotton, viscose, polyester, wool and leather have a minimal climate impact by 2030. Made. To meet current climate change commitments.

Claire Bergkamp, COO of Textile Exchange, said: “If business continues as usual, we expect growth (again) in 2030. The industry cannot stay on the 1.5C track without rethinking free growth. Both replacement and reduction, but it also requires innovation and partnerships to advance and scale known solutions.”

The need for concrete solutions is why the United Nations Fashion Charter last year added a requirement for signatories to submit appropriate emission reduction action plans. Do you have the internal and external support needed to make this happen? If you can’t achieve these goals? I’m talking about the questions being asked.

News

What’s Involved in the Personal Injury Claim Process

If you have sustained injuries because of another person’s negligence can file a personal injury claim to seek damages. However, it can feel complicated if it is your first time going through the claim process. Because of this, you can make mistakes. Sadly, even a simple mistake in this type of case can decrease your odds of securing compensation for your injuries. To avoid these mistakes, you should seek legal advice from an experienced personal injury attorney.

It’s not a legal requirement to hire an attorney to file an injury claim. However, hiring an attorney is usually the first step. The right lawyer can help you throughout each step of the process, which includes ensuring you have the right to sue. Below are the steps involved in the personal injury claim process:

Screening

As the injured party who wants to initiate a lawsuit, you must contact a lawyer for a consultation first. This allows you to talk about your case and the injuries you have suffered. During this consultation, the attorney may ask you to sign a document that authorizes them to access your medical records. The lawyer will ask about your insurance coverage, whether an insurance adjuster has contacted you, and what transpired during your conversation with them.

Once the lawyer accepts the case, they will thoroughly investigate the accident. This includes speaking with witnesses, collecting and preserving evidence, and contacting insurance companies.

Settlement Negotiations

Before you file a lawsuit, your lawyer will contact the insurance company of the at-fault party to determine if they can reach a fair settlement of your case before you to go court. Based on the circumstances and facts of your case, your lawyer drafts a demand letter with a settlement amount and send this to the insurance company. If both parties cannot reach an agreement, litigation can ensue.

Complaint Filing and Serving

Your lawyer will file the complaint with the court, triggering the litigation process. Then, the defendant will get a summons that notify them of your complaint and the amount of time they have to respond to it.

Discovery

During the discovery process, lawyers for both sides gather details and testimony, documents, and evidence related to the case. Discovery comes in the form of written discovery, depositions, and production of documents.

The discovery process is then followed by hiring expert witnesses, filing pre-trial motions, and going through mediation. These steps are meant to try to help both parties settle their case before going to trial. However, if they fail to resolve their issues during these steps trial will occur in court.

News

Hh gregg A Tale of Retail Resilience and Transformation

In the world of retail, few names are as iconic as hh gregg. This article delves into the fascinating journey of this retail giant, from its inception to its rebranding as Gregg’s, and the impact it left on the retail market.

| Heading | Subheading |

|---|---|

| Introduction | |

| The Rise and Fall | |

| Rebranding as Gregg’s | |

| Products and Services | |

| Customer Experience | |

| Online Presence | |

| Impact on Retail Market | |

| Conclusion |

Introduction

Once a household name in the electronics and appliances retail industry, hh gregg was known for its wide range of products and exceptional customer service. However, its story is not just one of success but also resilience and transformation.

The Rise and Fall

hh gregg’s rise to prominence was meteoric. Established in 1955 by Henry Harold Gregg and his wife, Fansy, as an appliance and electronics store in Indianapolis, Indiana, the company quickly expanded its footprint across the United States. With its commitment to delivering quality products and personalized service, hh gregg became a go-to destination for consumers seeking appliances, electronics, and more.

The fall of hh gregg, on the other hand, was equally dramatic. In 2017, the company filed for bankruptcy and subsequently closed all its stores. The reasons behind this decline were complex, including increased competition and changing consumer preferences.

Rebranding as Gregg’s

Despite the setback, the hh gregg story didn’t end there. The company underwent a remarkable transformation and rebranded itself as Gregg’s. This rebranding effort aimed to leverage the brand’s legacy while adapting to the changing retail landscape.

Products and Services

Gregg’s continued to offer a wide array of products, including appliances, electronics, and furniture. However, it also diversified into new categories such as smart home technology, emphasizing innovation and staying up-to-date with consumer demands.

Customer Experience

One thing that remained unchanged was Gregg’s commitment to customer experience. The brand focused on delivering exceptional service, ensuring that customers felt valued and supported in their purchasing decisions.

Online Presence

In the digital age, Gregg’s recognized the importance of an online presence. They invested in user-friendly websites and mobile apps, making it convenient for customers to browse, purchase, and track their orders from the comfort of their homes.

Impact on Retail Market

Gregg’s reentry into the retail scene had a significant impact. The company’s success story served as a beacon of hope for the retail industry, showcasing that reinvention and adaptation could breathe new life into even the most established brands.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the transformation of hh gregg into Gregg’s is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of retail brands. It demonstrates the importance of understanding customer needs and embracing change to thrive in an ever-evolving market.

FAQs

1. What led to hh gregg’s decline and bankruptcy?

The decline of hh gregg was influenced by factors like increased competition, changing consumer preferences, and financial challenges.

2. How did Gregg’s rebrand itself successfully?

Gregg’s successfully rebranded by diversifying its product offerings, focusing on customer experience, and establishing a robust online presence.

3. What products can I find at Gregg’s today?

Gregg’s offers a wide range of products, including appliances, electronics, furniture, and smart home technology.

4. How can I access Gregg’s online services?

You can easily access Gregg’s products and services through their user-friendly website and mobile app.

5. What can other retailers learn from Gregg’s transformation?

Other retailers can learn that adaptability and a customer-centric approach are key to surviving and thriving in the dynamic retail market.

News

Sonic Youth: The Revolutionary Band That Redefined Alternative Music

Sonic Youth was a groundbreaking band that emerged in the early 1980s and quickly became a significant influence on the alternative music scene. Combining elements of punk rock, noise, and experimental music, the band created a distinctive sound that challenged conventional ideas about music and paved the way for countless other artists to explore new sonic possibilities.

In this article, we will explore the history of Sonic Youth, their impact on the music world, and their enduring legacy. From their early days in New York City’s vibrant downtown scene to their final performance in 2011, we will examine the band’s journey and celebrate their contributions to alternative music.

Introduction to Sonic Youth

Sonic Youth formed in 1981 in New York City’s Greenwich Village, where they quickly established themselves as a force to be reckoned with in the underground music scene. The band consisted of Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo, Kim Gordon, and Steve Shelley, and their sound was characterized by dissonant guitars, unconventional song structures, and a willingness to experiment with noise and feedback.

Early Years and Rise to Fame

Sonic Youth’s early years were marked by a series of independent releases and collaborations with other artists. However, it was their 1988 album “Daydream Nation” that propelled them to international fame and critical acclaim. The album was hailed as a masterpiece and remains one of the most influential alternative albums of all time.

Sonic Youth’s Unique Sound

Sonic Youth’s sound was defined by their use of alternate guitar tunings, unorthodox playing techniques, and a willingness to experiment with noise and feedback. This approach was heavily influenced by avant-garde composers like John Cage and minimalists like La Monte Young. The band’s willingness to push the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in popular music helped to redefine the alternative music scene and paved the way for countless other artists to experiment with sound.

Sonic Youth’s Impact on Alternative Music

Sonic Youth’s impact on alternative music cannot be overstated. The band’s willingness to experiment with sound and push the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in popular music paved the way for countless other artists to explore new sonic possibilities. Bands like Nirvana, Pixies, and Sonic Youth’s own record label, SST Records, were all heavily influenced by the band’s unique sound and approach to music.

Sonic Youth’s Legacy

Sonic Youth’s legacy continues to live on in the music of countless other artists. The band’s willingness to experiment with sound and push the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in popular music helped to redefine the alternative music scene and paved the way for countless other artists to explore new sonic possibilities. Sonic Youth’s influence can be heard in the music of bands like My Bloody Valentine, Radiohead, and Arcade Fire, to name just a few.

Conclusion

Sonic Youth was a band that redefined what was possible in alternative music. Their unique sound, willingness to experiment with noise and feedback, and refusal to be bound by conventional song structures helped to pave the way for countless other artists to explore new sonic possibilities. Sonic Youth’s legacy continues to live on in the music of countless other artists, and their influence on alternative music will be felt for generations to come.

FAQs

- When did Sonic Youth form?

- Sonic Youth formed in 1981 in New York City’s Greenwich Village.

- Who were the members of Sonic Youth?

- The band consisted of Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo, Kim Gordon, and Steve Shelley.

- What was Sonic Youth’s unique sound?

- Sonic Youth’s sound was characterized by dissonant guitars, unconventional song structures, and a willingness to experiment with noise and feedback.

- What was Sonic Youth’s most influential album?

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoAdmiral casino biz login

-

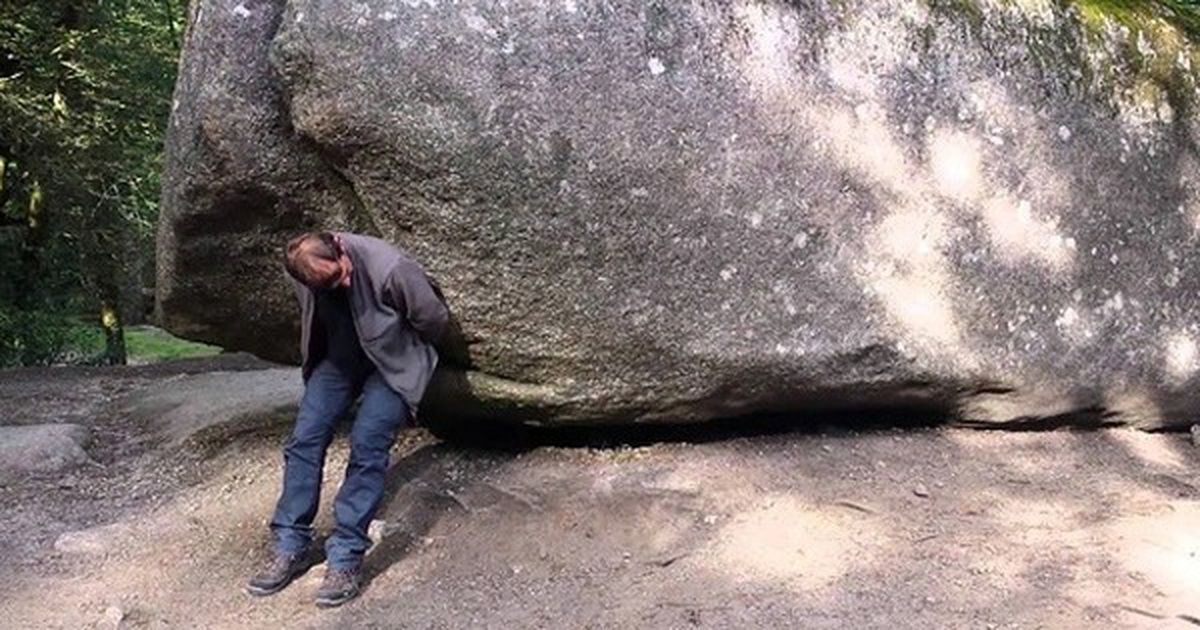

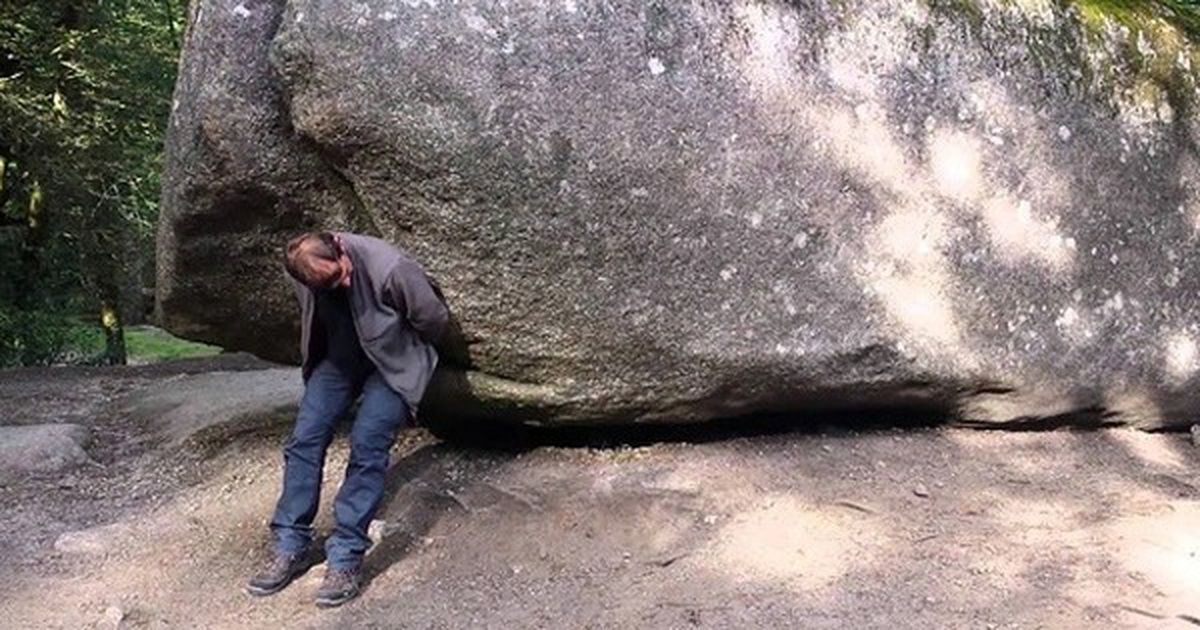

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoHow Much Does The Rock Weigh

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoDownload Popular Latest Mp3 Ringtones for android and IOS mobiles

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoTop 10 Apps Like MediaBox HD for Android and iPhone

-

LIFESTYLE2 years ago

LIFESTYLE2 years agoWhose Heartland?: The politics of place in a rural–urban interface

-

Fashion3 years ago

Fashion3 years agoHow fashion rules the world

-

Fashion Youth2 years ago

Fashion Youth2 years agoHow To Choose the Perfect Necklace for Her

-

Fashion Today2 years ago

Fashion Today2 years agoDifferent Types Of lady purse