Fashion

Fashion Brands Must Be Held Liable for Gender-Based Abuse | Opinion Fashion Brands Must Be Held Liable for Gender-Based Abuse | Opinion

Everyone has a right to be free from violence and harassment at work, including gender-based violence and harassment.

But for the millions of mostly women garment workers in the Global South, who toil for up to 16 hours a day on poverty wages to make our clothes, violence and harassment are a daily reality. Factory floors are plagued by allegations of discrimination, abuse and wage theft. For decades this abuse has been driven by an unequal and unsustainable power dynamic between brands and suppliers, which allows brands to reap financial benefits from workers’ labor at the lowest possible cost, creating and sustaining the conditions for widespread violence and harassment.

Unfortunately, this abuse only intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. As fashion brands canceled orders, delayed payments and squeezed suppliers further to protect profits, suppliers were often unable to pay workers their owed wages and made mass layoffs. Once lockdowns lifted, things only got worse; we spoke to 90 women garment workers from 31 factories across India—all of whom had recounted troubling stories of abuse during the pandemic.

Manisha, an Indian worker producing garments for international brands at a factory in Karnataka, explained, “During the COVID-19 lockdown, they did not pay us full wages. Then, when we returned to work, they increased production targets and abused us. If we were sick and needed to take leave, they would curse us. If we were unable to meet production targets, they would curse us. I do not want to revisit this time, even in my mind. The hunger, the abuse at home and in the factory, the deaths of loved ones, the feeling of gloom—this is what 2020 is to me.”

NEWSWEEK NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP >

Manisha’s story is not unique. Disturbingly, every woman we spoke to reported either directly experiencing or witnessing gender-based violence and harassment in their factories; often perpetrated by male supervisors driving them to meet unreasonable production targets set by fashion brands. Women spoke of routine physical, sexual and verbal abuse, discrimination and unfair dismissal, lack of protection from COVID-19 and intensified work rates leading to exhaustion and increased accidents.

Meena, a garment worker at a factory in Tamil Nadu, which produced clothes for C&A, Carrefour and Tesco, said threats of termination were “frequent” and workers who made even minor mistakes were “threatened aggressively.” She continued, “Verbal and physical harassment, including hitting and throwing bundles of clothes at women workers were more common during this period.”

This abuse wasn’t confined to the factory floor. Many suppliers resumed work before national lockdowns were lifted to avoid penalties imposed by brands for delays. Workers were forced to show up to work during lockdowns, leading to police harassment and violence during their commutes. Anita, employed at a factory in Delhi, said she was pushed to the ground and yelled at by the police when caught breaking lockdown orders on her way to work.

NEWSWEEK SUBSCRIPTION OFFERS >

The workers we spoke to made clothes for at least 12 global fashion brands including American Eagle, H&M, Primark and VF Corporation. These brands—like most—have policies prohibiting mistreatment and abuse in their supply chains, but at the same time squeeze their garment suppliers on price and speed to maximize profit margins, with women workers in the Global South paying the price

Gender-based violence and harassment doesn’t only affect workers producing for these brands; it’s an industry-wide problem, deeply embedded into the exploitative fashion business model. In Cambodia, nearly 1 in 3 women garment workers reported experiencing sexual harassment at work over a 12-month period. In Indonesia, 71 percent of women garment workers experienced gender-based violence at work, including verbal, sexual, psychological and physical abuse.

It’s time for fashion brands to be held legally accountable for the violence and abuse faced by the women workers who make their clothes and profits. Legally binding agreements can go a long way in protecting workers on the factory floor. Earlier this year H&M—along with labor groups Asia Floor Wage Alliance, Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union and Global Labor Justice-International Labor Rights Forum—signed a ground-breaking agreement after 20-year-old garment worker Jeyasre Kathiravel was allegedly raped and murdered at a H&M supplier factory in India. A recent investigation found that at least two other women were murdered at the factory, prior to Kathiravel.

If we are to transform workplaces in the garment sector, we also need international law on our side. Three years ago, women workers and trade unions won a hard-fought battle when the International Labour Organization adopted the Violence and Harassment Convention, which protects all workers, not just employees, and provided the first international definition of violence and harassment in the workplace. It also includes informal workers—largely poor women and migrants—who fall outside of social protections and are the most vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Unfortunately, only 11 countries have ratified this treaty in through their national laws—with the U.K. only doing so earlier this year.

OPINION

Everyone has a right to be free from violence and harassment at work, including gender-based violence and harassment.

But for the millions of mostly women garment workers in the Global South, who toil for up to 16 hours a day on poverty wages to make our clothes, violence and harassment are a daily reality. Factory floors are plagued by allegations of discrimination, abuse and wage theft. For decades this abuse has been driven by an unequal and unsustainable power dynamic between brands and suppliers, which allows brands to reap financial benefits from workers’ labor at the lowest possible cost, creating and sustaining the conditions for widespread violence and harassment.

Unfortunately, this abuse only intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. As fashion brands canceled orders, delayed payments and squeezed suppliers further to protect profits, suppliers were often unable to pay workers their owed wages and made mass layoffs. Once lockdowns lifted, things only got worse; we spoke to 90 women garment workers from 31 factories across India—all of whom had recounted troubling stories of abuse during the pandemic.

Manisha, an Indian worker producing garments for international brands at a factory in Karnataka, explained, “During the COVID-19 lockdown, they did not pay us full wages. Then, when we returned to work, they increased production targets and abused us. If we were sick and needed to take leave, they would curse us. If we were unable to meet production targets, they would curse us. I do not want to revisit this time, even in my mind. The hunger, the abuse at home and in the factory, the deaths of loved ones, the feeling of gloom—this is what 2020 is to me.”

NEWSWEEK NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP >

Manisha’s story is not unique. Disturbingly, every woman we spoke to reported either directly experiencing or witnessing gender-based violence and harassment in their factories; often perpetrated by male supervisors driving them to meet unreasonable production targets set by fashion brands. Women spoke of routine physical, sexual and verbal abuse, discrimination and unfair dismissal, lack of protection from COVID-19 and intensified work rates leading to exhaustion and increased accidents.

Meena, a garment worker at a factory in Tamil Nadu, which produced clothes for C&A, Carrefour and Tesco, said threats of termination were “frequent” and workers who made even minor mistakes were “threatened aggressively.” She continued, “Verbal and physical harassment, including hitting and throwing bundles of clothes at women workers were more common during this period.”

This abuse wasn’t confined to the factory floor. Many suppliers resumed work before national lockdowns were lifted to avoid penalties imposed by brands for delays. Workers were forced to show up to work during lockdowns, leading to police harassment and violence during their commutes. Anita, employed at a factory in Delhi, said she was pushed to the ground and yelled at by the police when caught breaking lockdown orders on her way to work.

The workers we spoke to made clothes for at least 12 global fashion brands including American Eagle, H&M, Primark and VF Corporation. These brands—like most—have policies prohibiting mistreatment and abuse in their supply chains, but at the same time squeeze their garments suppliers on price and speed to maximize profit margins, with women workers in the Global South paying the price. .

Fashion

Unveiling the Radiance of Thailand’s Beauty Industry: A Fashion Insider’s Perspective

In the realm of beauty and fashion, Thailand stands as a vibrant beacon of innovation, tradition, and exquisite taste. Having been immersed in the fashion world for decades, I have encountered myriad expressions of beauty across the globe. Yet, there is something inherently mesmerizing about Thailand’s beauty industry that invites a deeper exploration. This exploration reveals not just the external facets of beauty but also reflects the intricate tapestry of Thai culture and the burgeoning sectors of entertainment that subtly complement this industry.

A Mélange of Tradition and Innovation

At the heart of Thailand’s beauty industry lies the harmonious blend of age-old traditions and cutting-edge innovations. Thai beauty regimens, deeply rooted in natural remedies and herbal secrets passed down through generations, continue to inspire and shape modern skincare and makeup products. This reverence for the natural world translates into an array of products that celebrate organic ingredients, echoing the lush landscapes and rich biodiversity of Thailand.

Simultaneously, Thailand’s beauty scene is no stranger to innovation. Bangkok, a cosmopolitan hub buzzing with creative energy, is home to countless beauty startups and established brands that are making waves on the global stage. These brands are redefining beauty standards, championing diversity, and embracing the unique features that characterize the beauty of Southeast Asia.

Fashion and Beauty: A Synergistic Symphony

The synergy between fashion and beauty in Thailand is palpable. Walking through the bustling streets of Bangkok or the serene alleys of Chiang Mai, one is immediately struck by the impeccable style and the radiant skin of the locals. It’s a testament to how deeply interconnected fashion and beauty are, with each influencing and elevating the other. Thai fashion designers often collaborate with beauty brands to create holistic looks that capture the essence of Thai aesthetics — a blend of boldness, elegance, and authenticity.

The Allure of Nightlife and Refined Leisure

The Allure of Nightlife and Refined Leisure Featuring สล็อตเว็บตรง100

The beauty and fashion industries in Thailand are curiously complemented by the nation’s refined nightlife and leisure culture. Imagine an evening that begins with a visit to an opulent venue where the thrill of strategy and chance unfold in an environment of sophisticated design and discretion, akin to the allure found at สล็อตเว็บตรง100. Here, amidst the soft clinking of glasses and the murmurs of anticipation, beauty and fashion find additional expressions. As enthusiasts of fashion and beauty, individuals frequent these settings not just for the entertainment but for the opportunity to showcase their style, mingle with like-minded aficionados, and immerse themselves in an atmosphere where glamour and elegance reign supreme.

These venues, emblematic of Thailand’s vibrant entertainment landscape, serve as a testament to the Thai penchant for blending tradition with contemporary pursuits. They offer a space where the beauty industry’s influence extends beyond the daylight hours, contributing to the night’s allure and mystique, much like the captivating and elegant play at สล็อตเว็บตรง100.

Conclusion: Thailand’s Global Beauty Statement

Thailand’s beauty industry, with its deep cultural roots and innovative outlook, is making a significant mark on the global stage. For someone who has spent a lifetime in the world of fashion, witnessing Thailand’s beauty evolution is both inspiring and illuminating. The country not only celebrates beauty in its myriad forms but also seamlessly weaves it into the fabric of everyday life and the sophisticated dimensions of its entertainment culture. Thailand invites us to redefine beauty, embracing it as an art form, a reflection of cultural heritage, and a celebration of individuality.

Fashion

Fashion to Figure: Empowering Fashion for Every Body

Fashion is a dynamic expression of identity, and “Fashion to Figure” stands at the forefront of inclusive fashion. In this article, we’ll delve into the brand’s rich history, its impact on body positivity, the significance of its collections, and its role in shaping the fashion landscape.

I. Introduction

Definition of “Fashion to Figure”

Fashion to Figure is more than just a brand; it’s a movement that redefines fashion norms. Founded on the principles of inclusivity, this brand caters to diverse body types, ensuring everyone feels confident and stylish.

Significance in the Fashion Industry

In a world where body diversity is often overlooked, Fashion to Figure emerges as a trailblazer, challenging traditional beauty standards. Its significance lies not only in trendy clothing but in fostering a sense of empowerment for individuals of all shapes and sizes.

II. History of Fashion to Figure

Founding and Early Years

The journey of Fashion to Figure began with a vision to break barriers. Founded in [Year], the brand set out to address the limited options available for plus-size individuals, pioneering inclusivity in the fashion industry.

Evolution Over Time

As the years passed, Fashion to Figure evolved, adapting to changing tastes and societal demands. The brand’s commitment to diversity remained unwavering, influencing the broader fashion landscape.

III. Inclusivity in Fashion

Addressing Diverse Body Types

One of Fashion to Figure’s core principles is acknowledging and celebrating diverse body types. The brand’s sizing options cater to a wide range, ensuring that fashion is accessible to everyone.

Celebrating Diversity in Fashion

Fashion to Figure not only addresses inclusivity but celebrates it. The brand’s campaigns and runway shows emphasize the beauty of diversity, challenging stereotypes and promoting a positive body image.

IV. Fashion to Figure Collections

Overview of Current Collections

Fashion to Figure continually introduces collections that blend current trends with timeless styles. From casual wear to elegant evening attire, the brand offers a diverse range of options for every occasion.

Popular Items and Styles

Certain items and styles have become synonymous with Fashion to Figure’s identity. Explore the must-have pieces that have captured the hearts of fashion enthusiasts worldwide.

V. Online Shopping Experience

User-Friendly Website Design

Navigating the Fashion to Figure website is a seamless experience. Discover how the brand prioritizes user-friendliness, allowing shoppers to find the perfect pieces with ease.

Size-Inclusive Features

Online shopping can be challenging for plus-size individuals, but Fashion to Figure has implemented size-inclusive features to ensure a satisfying and confident shopping experience for all.

VI. Fashion Trends and Inspirations

Staying Current with Fashion Trends

Fashion to Figure stays on the pulse of ever-changing trends, ensuring its collections are always fresh and exciting. Explore how the brand keeps up with the fast-paced world of fashion.

Drawing Inspiration from Fashion to Figure

Whether you’re a fashion enthusiast or a designer, Fashion to Figure serves as a wellspring of inspiration. Discover how the brand’s designs influence and inspire the broader fashion community.

VII. Impact on Body Positivity

Promoting Self-Confidence

Fashion to Figure goes beyond clothing; it promotes self-confidence. Learn how wearing the brand’s designs contributes to a positive self-image and empowers individuals to embrace their unique beauty.

Empowering Individuals through Fashion

Through its commitment to body positivity, Fashion to Figure empowers individuals to express themselves authentically. Explore real-life stories of how the brand has made a significant impact on its customers.

VIII. Celebrity Collaborations

Notable Partnerships

Fashion to Figure has collaborated with influential figures in the entertainment and fashion industry. Discover the noteworthy partnerships that have shaped the brand’s identity.

Influence on Fashion Culture

Celebrity collaborations have not only elevated Fashion to Figure’s profile but also contributed to a broader shift in fashion culture. Explore the brand’s influence on industry trends and consumer preferences.

IX. Sustainability Efforts

Eco-Friendly Initiatives

In an era where sustainability is paramount, Fashion to Figure takes steps to minimize its environmental impact. Explore the brand’s eco-friendly initiatives and commitment to ethical fashion.

Commitment to Ethical Fashion

Beyond style, Fashion to Figure values ethical practices. Delve into the brand’s commitment to fair labor practices, responsible sourcing, and overall ethical considerations in the fashion industry.

X. Customer Reviews and Testimonials

Positive Feedback

The true measure of a brand’s success lies in its customers’ satisfaction. Read firsthand accounts of individuals who have experienced the confidence-boosting effects of Fashion to Figure.

Addressing Concerns and Improvements

While the brand receives praise, it’s essential to address any concerns and improvements. Explore how Fashion to Figure actively listens to its customers and continually strives for excellence.

XI. Social Media Presence

Engaging with the Fashion Community

Fashion to Figure understands the importance of social media in today’s digital age. Discover how the brand engages with its audience, fostering a vibrant and supportive fashion community.

Influencer Collaborations and Campaigns

Influencers play a pivotal role in shaping trends. Learn about Fashion to Figure’s collaborations with influencers and the impact these partnerships have on the brand’s reach and influence.

XII. Fashion to Figure in the Media

Features in Magazines and Blogs

Fashion to Figure has garnered attention from prominent media outlets. Explore the brand’s features in magazines and blogs, highlighting its influence on mainstream fashion discussions.

Interviews with Founders and Designers

Get a glimpse into the minds behind Fashion to Figure. Read exclusive interviews with the founders and designers, gaining insight into the brand’s philosophy and future aspirations.

XIII. Challenges and Resilience

Navigating Industry Challenges

No success story is without its challenges. Explore the obstacles Fashion to Figure faced and how the brand’s resilience and adaptability have contributed to its continued success.

Success Stories and Adaptations

From challenges arise success stories. Discover how Fashion to Figure’s ability to adapt and overcome obstacles has led to triumphs that resonate with its audience.

XIV. Future Outlook

Anticipated Developments

What does the future hold for Fashion to Figure? Explore anticipated developments, including potential expansions, collaborations, and innovations that will further solidify the brand’s place in the fashion industry.

Continued Commitment to Inclusivity

As Fashion to Figure looks to the future, its commitment to inclusivity remains unwavering. Learn about the brand’s ongoing efforts to break barriers and create a fashion landscape that truly embraces every body.

XV. Conclusion

In conclusion, Fashion to Figure isn’t just a brand; it’s a movement reshaping the fashion narrative. From its humble beginnings to its current status as a beacon of inclusivity, Fashion to Figure has made a lasting impact on the industry.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Is Fashion to Figure only for plus-size individuals? Fashion to Figure primarily focuses on providing inclusive fashion for all body types, including plus-size individuals. However, its collections are designed to cater to a wide range of sizes.

- How can I stay updated on Fashion to Figure’s latest collections? To stay informed about Fashion to Figure’s latest releases and updates, you can follow the brand on its official social media accounts and subscribe to its newsletter.

- Are Fashion to Figure’s clothing items affordable? Fashion to Figure offers a range of price points to cater to different budgets. The brand strives to provide stylish and inclusive fashion at accessible prices.

- Does Fashion to Figure ship internationally? Yes, Fashion to Figure offers international shipping, allowing fashion enthusiasts worldwide to access its diverse and inclusive collections.

- How can I share my feedback with Fashion to Figure? Fashion to Figure values customer feedback. You can share your thoughts and suggestions through the brand’s official website or social media channels.

Fashion

Y2K Fashion: A Nostalgic Resurgence in Style

The early 2000s, often referred to as the Y2K era, was marked by bold and flashy fashion trends that left an indelible mark on pop culture. Fast forward to today, and Y2K fashion is experiencing a remarkable revival. This article delves into the resurgence of Y2K fashion, exploring its trends, celebrity influence, key pieces, brands, everyday wear, social media impact, DIY aspects, events, controversies, and the future of this nostalgic style.

Y2K Fashion Trends:

Y2K fashion was characterized by its bold and extravagant styles. Think futuristic elements, metallic fabrics, and a playful mix of colors. The fashion of this era was a manifestation of the optimism and innovation that marked the turn of the millennium.

Celebrity Influence:

Celebrities play a pivotal role in shaping fashion trends, and the Y2K resurgence is no exception. Notable personalities are embracing the Y2K aesthetic, and their influence is reshaping the modern fashion landscape.

Key Y2K Pieces:

Mini skirts, rhinestones, and chunky platform shoes – these were the staples of Y2K fashion. We explore these iconic pieces and how they are making a comeback in the wardrobes of fashion enthusiasts.

Y2K Fashion Brands:

Several brands have taken the lead in the Y2K revival, capitalizing on the nostalgia associated with the era. Collaborations between brands and celebrities further fuel the resurgence of Y2K fashion.

Y2K Fashion in Everyday Wear:

The Y2K style isn’t just reserved for special occasions. Learn how individuals are incorporating Y2K elements into their daily outfits, striking a balance between the old and the new.

Social Media Impact:

The rise of Instagram and TikTok has provided a platform for Y2K fashion to thrive. Influencers are setting the tone, showcasing their take on Y2K style and inspiring millions.

DIY Y2K Fashion:

For those who want a personal touch, DIY Y2K fashion is gaining popularity. Discover how enthusiasts are creating their own Y2K-inspired pieces while embracing sustainability in the process.

Y2K Fashion Events and Shows:

From runway shows to themed events, the fashion industry is celebrating the Y2K aesthetic. We explore how events and shows are contributing to the resurgence of Y2K fashion.

Critics and Controversies:

As with any trend, Y2K fashion has its critics. We address opinions on the revival and delve into controversies surrounding the appropriation of styles from the past.

Future of Y2K Fashion:

What does the future hold for Y2K fashion? We discuss the sustainability aspect of future Y2K trends and how the style is evolving to meet the demands of a changing world.

Unveiling the Y2K Aesthetic

In the ever-evolving landscape of fashion, trends from the past often find their way back into the spotlight. Y2K fashion is one such nostalgic resurgence that has taken the style world by storm. Defined by its bold, futuristic, and often eccentric aesthetic, Y2K fashion encapsulates the essence of the early 2000s, bringing back memories of iconic pop culture moments.

The Rise of Y2K Fashion Icons

The Influential Icons: During the Y2K era, fashion icons emerged, leaving an indelible mark on the industry. Celebrities like Britney Spears, Paris Hilton, and Justin Timberlake became synonymous with the Y2K aesthetic, influencing a generation with their daring style choices. Today, their impact is reflected in the resurgence of spaghetti straps, cargo pants, and bedazzled accessories.

Key Elements of Y2K Fashion

Futuristic Fabrics and Metallic Hues

Shimmering Revival: Y2K fashion is characterized by its embrace of futuristic fabrics and metallic hues. Shiny and iridescent materials create a sense of otherworldly glamour, reflecting the technological optimism of the early 2000s. Incorporating metallic elements into your wardrobe instantly adds a touch of Y2K flair, capturing the essence of a bygone era with a modern twist.

Logomania: Branded Fashion Takes Center Stage

Branding Brilliance: Logo-centric clothing was a hallmark of Y2K fashion. Logomania, the trend of prominently featuring brand logos on clothing, symbolized a cultural shift towards consumerism and brand awareness. Today, fashion enthusiasts are rediscovering the allure of logo-heavy pieces, celebrating the bold branding that defined the Y2K era.

How to Embrace Y2K Fashion Today

Thrifting for Timeless Treasures

Thrifting Triumphs: One of the most sustainable and budget-friendly ways to embrace Y2K fashion is through thrift shopping. Thrifting for Y2K-inspired pieces not only adds unique finds to your wardrobe but also contributes to a more eco-conscious approach to fashion. Seek out nostalgic gems like cargo pants, mini skirts, and bedazzled accessories to curate an authentic Y2K look.

DIY Customization for a Personalized Touch

Expressive DIY: Y2K fashion encourages self-expression, and what better way to embody this spirit than through DIY customization? Transform plain pieces into Y2K masterpieces by adding rhinestones, patches, or playful embellishments. Unleash your creativity to capture the essence of the DIY movement that defined the early 2000s.

Y2K Fashion in Contemporary Runways

Influence on High-End Designers

High-End Homage: The Y2K aesthetic has transcended nostalgia and influenced high-end designers on contemporary runways. Prominent fashion houses have incorporated Y2K-inspired elements into their collections, solidifying the style’s status as a timeless and influential force. From holographic fabrics to futuristic silhouettes, Y2K continues to shape the trajectory of high-end fashion.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the Y2K fashion revival is more than just a nostalgic trip down memory lane. It’s a dynamic movement shaping contemporary fashion. The boldness and innovation of Y2K style continue to resonate, leaving a lasting impact on the fashion industry.

FAQs

- Is Y2K fashion only about bold and flashy styles?

- While bold and flashy styles are characteristic of Y2K fashion, it also includes futuristic elements and a mix of colors.

- How are celebrities influencing the Y2K fashion revival?

- Celebrities are embracing Y2K fashion, setting trends and influencing the industry through their fashion choices.

- Can I incorporate Y2K elements into my daily wardrobe?

- Absolutely! Y2K fashion can be seamlessly integrated into daily wear by mixing iconic pieces with modern styles.

- Are there sustainable aspects to Y2K fashion?

- Yes, the DIY trend in Y2K fashion often emphasizes sustainability, promoting creativity and eco-friendly practices.

- What’s the future of Y2K fashion?

- The future of Y2K fashion involves a focus on sustainability and an evolution of the style to adapt to changing fashion landscapes.

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoAdmiral casino biz login

-

Entertainment2 years ago

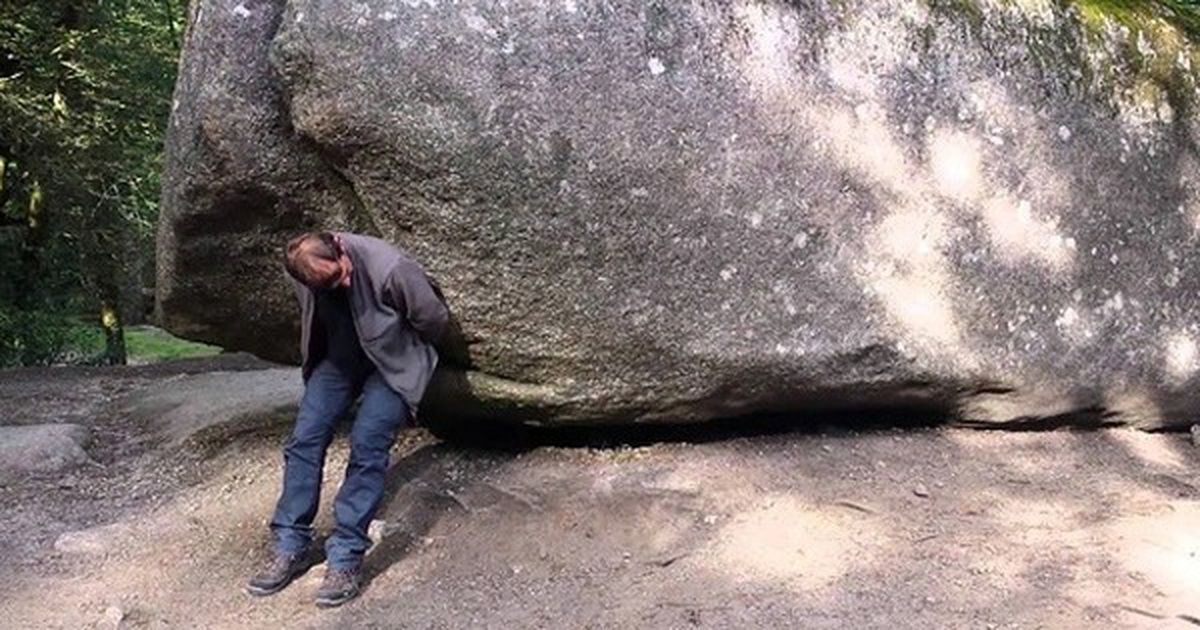

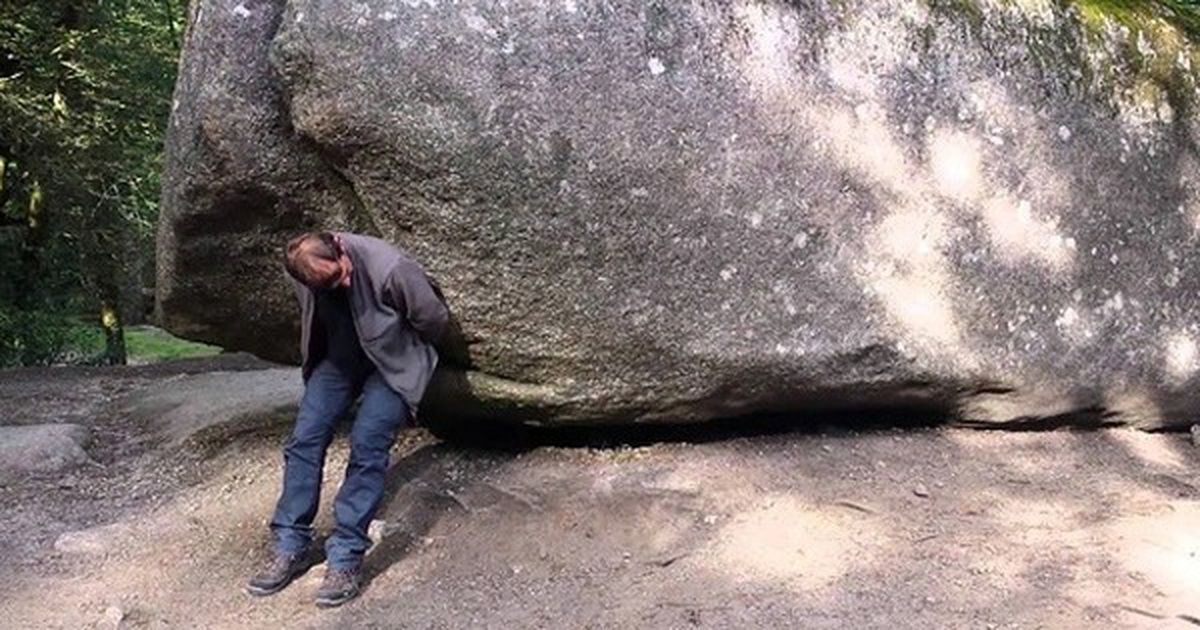

Entertainment2 years agoHow Much Does The Rock Weigh

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoDownload Popular Latest Mp3 Ringtones for android and IOS mobiles

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoTop 10 Apps Like MediaBox HD for Android and iPhone

-

LIFESTYLE2 years ago

LIFESTYLE2 years agoWhose Heartland?: The politics of place in a rural–urban interface

-

Fashion3 years ago

Fashion3 years agoHow fashion rules the world

-

Fashion Youth2 years ago

Fashion Youth2 years agoHow To Choose the Perfect Necklace for Her

-

Fashion Today2 years ago

Fashion Today2 years agoDifferent Types Of lady purse